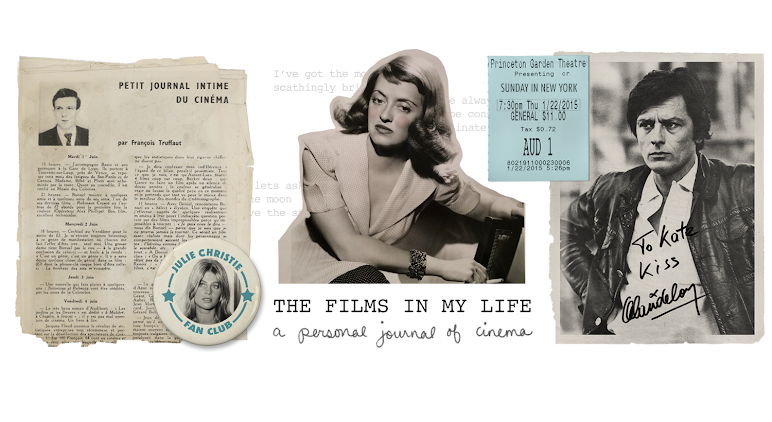

Guest Blogger

She was first given the most common of names – Gladys Smith—in Toronto,, Canada in 1882. She was born into poverty which got worse before it got better. Her father, john, worked idly as a handyman and drunk before leaving the family altogether in 1895. Her mother, Charlotte, began working as a seamstress and laundrywoman to support the family, finally taking in borders. She had two siblings, Jack and Lottie, both lazy, promiscuous drunks and sporadic actors; both of which followed her throughout their lives, living under her trellises like ungrateful parasites.

If some scribe during the silent era had ever dared describe her family as the above, they would have paid with their careers. Not only from Pickford’s wrath, which was formidable, but also from the reaction of an adoring public that embraced Gladys Smith in a way unprecedented. They loved her; intimately and very personally. Certainly today no star is so loved by so many, or ever will be. Film fans now for the most part are merely media fans - nothing but cannibals; and they are always starving. Sooner or later, everyone is eaten alive. But let’s not rant, and I’ve gotten ahead of myself.

Pickford ate the pedals of roses as a small girl, hoping to absorb their beauty, hoping to bring forth something within herself far beyond the subservient stink and steam of other people’s laundry; more than the grit of their floors ground into her bare knees. At six and seven she was cleaning other people’s rooms in her mother’s house. One of Charlotte’s borders were a family of theater people, and through them Mary was introduced to small parts on the local stage. Charlotte, naturally was horrified. Actresses were at best regrettable borders, barely higher on the rung than street walkers. Momma, said Mary, they will pay me. Really? Well, perhaps a few small, angelic roles would be all right after all; under mother’s close supervision, of course.

Something in the theater began to bring the roses forth. It brought something else to the fore as well, some powerful steel core or burning engine that began to drive her. Mary and mother began touring with minor league touring companies and plays. When she was 8 her mother walked her down to the Princess Theater, hoping to get her daughter cast in one of the small roles in the current production, The Silver Kings. The moment Charlotte presented Mary to the theater manager (Anne Blancke), Pickford suddenly spoke up and asked to play the female lead. Charlotte, seeing a paycheck flitter away, began apologizing for her daughter, who due to lack of schooling couldn’t read and surely couldn’t memorize all the lines.

Pickford stepped passed her mother, searched the face of the theater manager. She took the older woman’s hand – held it firmly. “Please, lady,” she said. “Let me try.”

Eventually her burning engine drove her to the attentions of theater legend, David Belasco (where she changed her name to Mary Pickford), then next to Biograph Company and D.W. Griffith. If theater performers were considered marginal, women and men that performed for the “flickers” were rock bottom. Women beyond the pale of decent society made their bold mark in the early days of silent motion pictures, which were then still considered a kind of freak sideshow; something to point and laugh at, shown at local carnivals or back-alley theaters.

Griffith saw something in Pickford, something he had been yearning for: An acting style that was different from the theatrical grand gesture then common – a thing much more subtle; smaller, yes, but far more personal and moving. Pickford’s acting, so full of the perfect, small expression, cried for close-ups. Pickford was among the first actors to ever act for the camera instead of acting for an audience. That is, she was performing for that single person who watched her closely – not the remote crowd. Griffith loved her, but wouldn’t allow her to flourish. For a few years she bounced back and forth between Griffith’s Biograph Company and Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures, never quite satisfied with either.

In 1913 she began making pictures for Adolph Zukor and his Famous Players. Under Zukor, she became a star after Tess of the Storm Country. And not just a star. Soon, only Charlie Chaplin could rival Pickford for popularity. No other actress was even in the conversation, and throughout the remainder of the 1910’s and into the 1920’s she became the most famous and powerful woman in the world. Indeed, she was often referred to by the press as the most famous woman in history. Her dominance was such that when she signed a new contract in 1916 with Zukor, she demanded and received full creative control over the motion picture projects she would select for herself and star in.

Her production under Zukor became screen history: Sparrows, Pollyanna, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Little Lord Fauntleroy, Daddy Long Legs, Stella Maris, etc., any one of which would have secured her an immortal niche. Her curls became something far more than a simple hair style; they became beautiful ribbons of purity – symbols of human goodness. She and husband Douglas Fairbanks entertained kings, and queens, scientists and flappers, at their castle called Pickfair. George Bernard Shaw was a frequent guest, as was Einstein. H.G. Wells swapped tales with F. Scott Fitzgerald over the dinner table.

Yet every reign has its day, every Caesar his Ides of March. When sound came to film the party was over. Pickford said, “adding sound to motion pictures is like putting lipstick on Venus De Milo.” She cut her hair into a bob and learned what every person in the world learns at some time: her time for “becoming” was over.

Yet it hardly mattered. She had succeeded, fulfilled some promise the little girl that ate the roses had made with herself. That bright, white engine within her could rest in comfortable retirement. For it was never fame or riches that drove her, though she enjoyed both immensely. No, she had been a serving girl without much in life, looking at the finery of others; and that made the engine burn.

Milton wrote “Better to rule in Hell than serve in Heaven.” Pickford’s engine, that iron bar of resolve that demanded only the chance to try, wanted something more. Pickford decided to create her own Heaven, Hollywood, where she could rule and serve no one.

She was first given the most common of names – Gladys Smith—in Toronto,, Canada in 1882. She was born into poverty which got worse before it got better. Her father, john, worked idly as a handyman and drunk before leaving the family altogether in 1895. Her mother, Charlotte, began working as a seamstress and laundrywoman to support the family, finally taking in borders. She had two siblings, Jack and Lottie, both lazy, promiscuous drunks and sporadic actors; both of which followed her throughout their lives, living under her trellises like ungrateful parasites.

If some scribe during the silent era had ever dared describe her family as the above, they would have paid with their careers. Not only from Pickford’s wrath, which was formidable, but also from the reaction of an adoring public that embraced Gladys Smith in a way unprecedented. They loved her; intimately and very personally. Certainly today no star is so loved by so many, or ever will be. Film fans now for the most part are merely media fans - nothing but cannibals; and they are always starving. Sooner or later, everyone is eaten alive. But let’s not rant, and I’ve gotten ahead of myself.

Pickford ate the pedals of roses as a small girl, hoping to absorb their beauty, hoping to bring forth something within herself far beyond the subservient stink and steam of other people’s laundry; more than the grit of their floors ground into her bare knees. At six and seven she was cleaning other people’s rooms in her mother’s house. One of Charlotte’s borders were a family of theater people, and through them Mary was introduced to small parts on the local stage. Charlotte, naturally was horrified. Actresses were at best regrettable borders, barely higher on the rung than street walkers. Momma, said Mary, they will pay me. Really? Well, perhaps a few small, angelic roles would be all right after all; under mother’s close supervision, of course.

Something in the theater began to bring the roses forth. It brought something else to the fore as well, some powerful steel core or burning engine that began to drive her. Mary and mother began touring with minor league touring companies and plays. When she was 8 her mother walked her down to the Princess Theater, hoping to get her daughter cast in one of the small roles in the current production, The Silver Kings. The moment Charlotte presented Mary to the theater manager (Anne Blancke), Pickford suddenly spoke up and asked to play the female lead. Charlotte, seeing a paycheck flitter away, began apologizing for her daughter, who due to lack of schooling couldn’t read and surely couldn’t memorize all the lines.

Pickford stepped passed her mother, searched the face of the theater manager. She took the older woman’s hand – held it firmly. “Please, lady,” she said. “Let me try.”

Eventually her burning engine drove her to the attentions of theater legend, David Belasco (where she changed her name to Mary Pickford), then next to Biograph Company and D.W. Griffith. If theater performers were considered marginal, women and men that performed for the “flickers” were rock bottom. Women beyond the pale of decent society made their bold mark in the early days of silent motion pictures, which were then still considered a kind of freak sideshow; something to point and laugh at, shown at local carnivals or back-alley theaters.

Griffith saw something in Pickford, something he had been yearning for: An acting style that was different from the theatrical grand gesture then common – a thing much more subtle; smaller, yes, but far more personal and moving. Pickford’s acting, so full of the perfect, small expression, cried for close-ups. Pickford was among the first actors to ever act for the camera instead of acting for an audience. That is, she was performing for that single person who watched her closely – not the remote crowd. Griffith loved her, but wouldn’t allow her to flourish. For a few years she bounced back and forth between Griffith’s Biograph Company and Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures, never quite satisfied with either.

In 1913 she began making pictures for Adolph Zukor and his Famous Players. Under Zukor, she became a star after Tess of the Storm Country. And not just a star. Soon, only Charlie Chaplin could rival Pickford for popularity. No other actress was even in the conversation, and throughout the remainder of the 1910’s and into the 1920’s she became the most famous and powerful woman in the world. Indeed, she was often referred to by the press as the most famous woman in history. Her dominance was such that when she signed a new contract in 1916 with Zukor, she demanded and received full creative control over the motion picture projects she would select for herself and star in.

Her production under Zukor became screen history: Sparrows, Pollyanna, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Little Lord Fauntleroy, Daddy Long Legs, Stella Maris, etc., any one of which would have secured her an immortal niche. Her curls became something far more than a simple hair style; they became beautiful ribbons of purity – symbols of human goodness. She and husband Douglas Fairbanks entertained kings, and queens, scientists and flappers, at their castle called Pickfair. George Bernard Shaw was a frequent guest, as was Einstein. H.G. Wells swapped tales with F. Scott Fitzgerald over the dinner table.

Yet every reign has its day, every Caesar his Ides of March. When sound came to film the party was over. Pickford said, “adding sound to motion pictures is like putting lipstick on Venus De Milo.” She cut her hair into a bob and learned what every person in the world learns at some time: her time for “becoming” was over.

Yet it hardly mattered. She had succeeded, fulfilled some promise the little girl that ate the roses had made with herself. That bright, white engine within her could rest in comfortable retirement. For it was never fame or riches that drove her, though she enjoyed both immensely. No, she had been a serving girl without much in life, looking at the finery of others; and that made the engine burn.

Milton wrote “Better to rule in Hell than serve in Heaven.” Pickford’s engine, that iron bar of resolve that demanded only the chance to try, wanted something more. Pickford decided to create her own Heaven, Hollywood, where she could rule and serve no one.

4 comments:

Kate: Wonderful, wonderful work. -- Mykal

I never knew all that about Mary, great post Mykal and amazing job on the painting of Mary Kate!

That's wonderful! And the painting is just gorgeous!

I really love your pop art! Fatty, Theda, and Louise are my favorites. Don't be surprised if I snatch them away from your collection soon ;)

Post a Comment